|

|

THE LOST GODS OF GERMANY

|

Prior to the discovery and

dissemination of the Poetic Edda in 1643, these were the best

reports of the Gods of Northern Europe. The first translation

and full printing of the Eddic poems would not occur until

1787-1812. Thus Arnkeil's work gives us a glimpse of what the

Germanic pantheon looked like in the popular mind, before the

Codex Regius had been found.

Besides discussing the Gods of the Germanic tribes, as known at

the time, this book contains information and illustrations

of divinities and fantastic creatures from other world

mythologies. Here I have only included the images of the

dieties in the Germanic sphere. Some of the illustrations in

this book appear

to be based on those in Elias Schedius'

De Diis Germanis (1648). Some of these gods are familiar to

us and

others are not. Where the author cites a source for a deity, I

have provided the reference and any additional information where

possible.

The illustrations herein remained influencial into the early decades

of the 19th century, reprinted in other works or in derivative

form (see below).

|

Title Page |

THOR,

ODIN, FREIA

This image (left) is based on an

illustration from manuscript Nks 1867 4to of Snorri's

Edda (right). As told in the opening

scene of Gylfaginning, Swedish King Gylfi, in disguise

as Gangleri, questions

Hárr, Jafnhárr, and

Þriði— High, Just-as-High, and Third—presumably a threefold representation of Odin himself. The

author demonstrates his very limited knowledge of Snorri's Edda

beginning on page 86.

|

OTHIN, THOR, FRIGGE

These images of

Odin, Thor and Frigg are based on a woodcut first published in

Olaus Magnus'

A Description of the Northern Peoples

(1555), which

also inspired

Richard Verstegan's Saxon Idols in Restitution of Decayed Intelligence in

Antiquities

(1605).

|

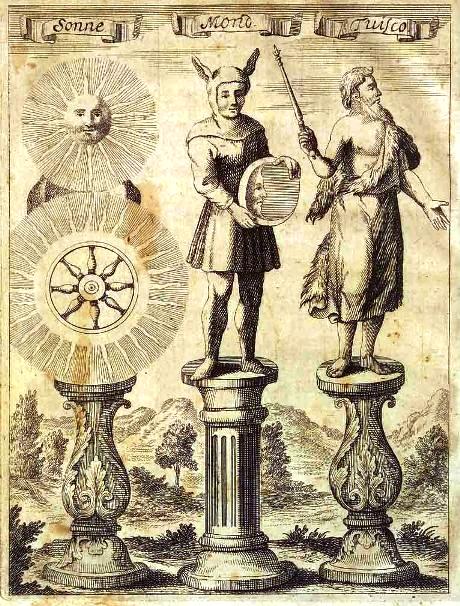

The Saxon Gods: The Namesakes of the Weekdays

Sun, Moon, Tuisco, Wodan, Thor (not

pictured), Freyja, Seater

|

THE GOLDEN HORN

The illustrated horn clearly shows images of mythic

beings and creatures, including the lady with the mead

cup, twin gods, a three-headed giant, and animal-headed

beings. This is a drawing of the first of

two golden horns known today as the Gallehus Horns found

in 1639 and 1734. This horn, the longer of the two, had

seven segments with ornaments, to which six plain

segments and a plain rim were added, possibly in the

17th-century by a restorer. Both of the original horns

were stolen in 1805 and melted down.

|

|

FRO, MITOTHIN and VAGNHOFF

These images of

Freyr (Fro), Mitothin, and Vagnoff are based on a

woodcut from Olaus Magnus'

A Description of the Northern Peoples

(1555). Their names characters ultimately derive

from figures found in Books I-IX of Saxo

Grammaticus' Danish History. These gods are not

clearly identified in the original, however the text

appears to indicate that the first figure is

Mitothin, chief priest of the gods, and the second

is Freyr, a deputy of the gods. The name of the

third figure, Vagnoff, is probably a misreading of

Vagnhofthi, a giant who assists Hadding in the first

Book of Saxo's Danish History.

See Also Richard Verstegan's

Restitution of Decayed Intelligence in

Antiquities

(1605)

|

|

THE SAXON IRMINSUL

An Image of Mercury, also called Wodan

This image of the god Irminsul (left) is

clearly based on Conrad Bote (also called Botho)'s image of the Idol

Armesule in his Saxon Chronicle of 1492 (right):

These, in turn, appear to be related to an

illustration from Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia c. 1590

(right),

depicting a god of war and commerce:

His inspiration for this is likely a reference

in the 12th century

Kaiserchronik, concerning

the origin of the designation Wednesday and

therefore probably describing the god Woden

(Odin), which reads:

| |

- ûf ainer

irmensiule

- stuont ain

abgot ungehiure,

- daz hiezen

si ir choufman.

|

"On an Irminsul

stands an enormous idol

which they call their merchant." |

|

An Irminsul is properly a kind of

pillar attested as an object of worship among the

ancient Saxon tribes. From this, a Germanic god Irmin,

inferred from the name Irminsul and the tribal name

Irminones, was once presumed to have been the national

god of the Saxons. The first reference to an Irminsul,

as the chief seat of the Saxon religion, appears in the

Royal Frankish Annals (772AD). During the Saxon wars,

Charlemagne repeatedly orders its destruction.

The Irminsul is described as located near Heresburg (now

Obermarsberg), Germany. Rudolf of Fulda (AD 865)

provides a description of an Irminsul in his De

Miraculis Sancti Alexandri ("The Miracles of Saint

Alexander"), chapter III, where he describes the

Irminsul as a great wooden pillar erected and worshipped

under the open sky.

A surprisingly late source

identifies the Irmunsul with an idol of the Roman God

Mercury, often identified as Woden or Odin in Medieval

European histories. The source links the Germanic god

Mercury directly to Frau Herra (a form of the name

Herke) as deities worshipped together by the ancient

Saxons. As such it’s worth quoting at length. The

author is Gobelin Person (also Gobelinus Persona,

1358-1421), a prominent historian and church reformer

from the bishopric of Paderborn, in North

Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. His main work, Cosmidromius,

completed in 1418, prior to the re-discovery and

dissemination of a single manuscript of Tacitus’

Germania in 1425, is one of the most important

historical works of the 15th century. In chapter 38,

written some time before 1406, speaking of local history

and superstition, he writes:

| |

"Charles the Great in the year of

our Lord 769, took hold of the reign in the

kingdom of the Franks and ruled for

forty-six years; of course, three years

together with his brother Carlomann and the

remainder of the years ruled alone. In the

second year of his reign, the General

Assembly of Worms convened to decide upon

the approach to the Saxon War, and they,

without delay, advanced altogether with

swords and fire to plunder the castle of

Eresburgh, which presently is called Mount

Mars in the Latin tongue, and seized the

idol which the Saxons call Irminsuel,

destroyed it and then took it back all the

way up to the Weser River, and withdrew with

twelve Saxon hostages. Understand that this

idol Irminsuel is Mercury or what the Greeks

call Hermes ... They consecrate the idol or

statue in the aforementioned place to this

god, because Irminsuel is a statue of he who

is called Hermes. And because in this

aforementioned place all men in the district

assemble in order to sacrifice to the idol

out of reverence and devote themselves to

it, that place is called Eresburgh, the

Mountain of Reverence. Actually, Juno, who

is called in the writings of the Greeks

Hera, was worshipped in the same place

before Hermes or perhaps at the same time,

thereupon they call that place Heresbergh,

which is clearly the Mountain of Hera or

Juno, and afterwards, when they occupied and

fortified that place, call it Heresburgh,

the Castle of Hera Veneration. Moreover,

this Hera was worshipped by the Saxons,

which can be seen by the fact that certain

of the common people recite what they

themselves have heard from the antiquity,

just as I myself have heard, that between

the festival of the Birth of Christ and the

holiday of the Epiphany of the Lord,

Mistress Hera flies through the air, because

the pagans assign the air to Juno. And

because Juno, whenever they call upon her as

Ceres and depict her with bells and wings,

the common people call her vrowe here (Frau

Here), or corrupt the name Vor Here de

Vlughet [of Flight], and believe that she

herself brings abundance at that time."

|

|

The significance of this

remarkable passage cannot be overstated. Written

prior to the discovery of Tacitius’ Germania in

1425, it clearly identifies a local Saxon god

with the Roman Mercury, information which can be

gleaned from only a few other sources. He

appears to speak of local belief recording what

“certain of the common people” say they

“themselves have heard from antiquity [or the

ancient elders], just as I myself have heard.”

Although he travelled widely throughout Italy in

the company of Pope Urban VI before being

ordained in 1386, Gobelin Person was a native of

Paderborn, Germany who was born, lived, worked,

and ultimately buried in the vicinity. Although

deeply learned, he was in a position to both

know and understand local legend. Remarkably, he

not only identifies the local Saxon goddess

known as Frau Herre with the Greek goddess Hera,

the Queen of the Classical pantheon, but also

with Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture,

demonstrating that the identification was based

on more than just a superficial similarity

between the names Herre and Hera. Clearly

drawing on local tradition which he himself has

heard, he says the common folk believe she flies

through the air at Christmas time bringing

abundance, adding the unique detail that she is

depicted with bells and wings. These details

immediately correspond to what we know of Frau

Holle, whose followers are known for ringing

bells, and her wings can be confirmed by images

in iconography and the mythology of the region,

which is well-acquainted with prophetic

goddesses in the form of birds. In addition,

Gobelin directly associates her worship with the

Classical god Hermes or Mercury, who is widely

recognized as Odin from other sources, and this

at least two decades before the re-discovery and

wide dissemination of Tacitus’ book on the

traits and traditions of the Germanic tribes! In

addition, he precisely pinpoints the time of her

flight as taking place between the Feast of the

Nativity and the Feast of the Epiphany,

corresponding to the Twelve Days of Christmas,

the exact time of the Wild Hunt in Northern

European belief.

All copies of Germania were lost during the

Middle Ages and the work was forgotten until a

single manuscript was found in Hersfeld Abbey

(Codex Hersfeldensis) in 1425. It was then

brought to Italy, where Enea Silvio Piccolomini,

later Pope Pius II, first examined and analyzed

the book. This sparked interest among German

humanists, including Conrad Celtes, Johannes

Aventinus, and Ulrich von Hutten and beyond. The

peoples of medieval Germany (the Kingdom of

Germany in the Holy Roman Empire) were

heterogenous, separated in distinct tribal

kingdoms, such as the Bavarians, Franconians,

and Swaibians, distinctions which remain evident

in the German language and culture after the

unification of Germany in 1871 and the

establishment of modern Austria and Germany.

During the medieval period a self-designation of

"Germani" was virtually never used, the name was

only revived in 1471, inspired by the

rediscovered text of Germania, to invoke the

warlike qualities of the ancient Germans in a

crusade against the Turks. Ever since its

discovery, treatment of the text regarding the

culture of the early Germanic peoples in ancient

Germany remains strong especially in German

history, philology, and ethnology studies, and

to a lesser degree in Scandinavian countries as

well.

For additional contemporary information on

Irminsul (Mercury) and Hera, see

Petrus Albinus,

Saxonum Historiue Progymnasmata, 1585

|

THE

GODDESS HERTHA

MOTHER

EARTH |

|

|

An illustration of the goddess Herthe known

from chapter 40 of Tacitus' Germania (c. 90AD)

which reads:

“The Langobardi are distinguished by

being few in number. Surrounded by many mighty

peoples they have protected themselves not by

submissiveness, but by battle and boldness. Next to

them come the Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini,

Eudoses, Suarines and Huitones protected by rivers

and forests. There is nothing especially noteworthy

about these states individually, but they are

distinguished by a common worship of Nerthus, that

is, Mother Earth, and believe she intervenes in

human affairs and rides through their peoples. There

is a sacred grove on an island of the Ocean, in

which there is a consecrated chariot draped with a

cloth, which the priest alone may touch. He

perceives the presence of the goddess in the

innermost shrine and with great reverence escorts

her in her chariot, which is drawn by female cattle.

There are days of rejoicing then and the countryside

celebrates the festival, wherever she deigns to

visit and to accept hospitality. No one goes to war,

no one takes up arms. All objects of iron are locked

away then and only then do they exercise peace and

quiet, only then do they prize them, until the

goddess has had her fill of society, and the priest

brings her back to the temple. Afterwards the

chariot, the cloth, and if one may believe it, the

deity herself are washed in a hidden lake. The

slaves who perform this office are immediately

afterwards swallowed up in the same lake. Hence

arises dread of the mysterious, and piety, which

keeps them ignorant of what only those who are about

to perish may see.” [—A.R.

Birley translation, 1999]

Prior to the work of modern scholars who

consider the reading Nerthum the most

accurate, this goddess was commonly known as

Herthus or Herthe based on a variant

reading found in some manuscripts. John McKinnell,

writing in Meeting the Other in Norse Myth and

Legend (2005), explains:

“The usually accepted stemma has three families, and

readings shared by the best manuscripts of any two

of them are thought likely to be correct. The best X

group manuscripts (Vatican, Cod. Vat. 1862, Leiden

UL XVIII Periz.Q.21) read Neithum; the best y

manuscripts (Cod. Vat. 1518, Codex Neapolitanus)

have Nerthum, and the best Z manuscript (Iesi,

Æsinas Lat. 8) reads Nertum. The sound /th/ did not

exist in classical Latin, though the spelling is

found in words derived from Greek or the Germanic

languages (such as thesaurus 'treasure', or the name

Theodoricus). Tacitus would therefore be unlikely to

introduce the spelling th gratuitously. In the

fifteenth century, the Italian scribes who produced

most of the earliest surviving manuscripts

(including the Iesi manuscript) would have a natural

tendency to replace th with t, as was consistently

done in their native language (see Italian tesoro,

Teodorico), but would be very unlikely to do the

reverse. Nerthum is therefore more probably correct

than Nertum. If both Y and Z should read Nerthum,

that reading must be preferred. A different stemma,

proposed by Robinson, has only two groups, and the

best manuscripts in both read Nerthum. Whichever

stemma is correct, Nerthum therefore seems the

likeliest reading, although it could represent

either a grammatically masculine Nerthus or a

grammatically neuter Nerthum.”

|

|

|

The

form Hertha is a false reading of comparatively modern origin.

In 1519, Rhenanus, the pious scholar who published Tacitus,

wrote Herthum for Nerthum, manifestly the same as the Old High

German Herda, earth. Based on his authority, the text of

Tacitus was uniformly given as Herthum up until 1817, when

editors such as Franz Passow restored Nerthum to the Latin text.

That the name Nerthus is grammatically masculine in form has

lead some critics such as Klaus von See

to conclude that Tacitus had no genuine information about the

cult of Nerthus other than this name, and therefore based his

account of the Germanic ‘god’ on the Roman cult of Magna Mater

(the Great Mother), a cult in which Tacitus was himself entitled

to participate.

Therefore, the most frequent objections to the authenticity of

the Nerthus cult are based upon superficial comparisons to its

Roman reflection, almost always ignoring their sharp contrasts.

Besides the superficial similarity of the designations Terra

Mater and Magna Mater, or more properly magna deum mater, “great

mother of the gods,”

scholars prone to compare the two point out the fact that both

cults included a public procession which terminated with the

ritual washing of the idol in a lake. The differences between

these cults, however, are not insignificant, and thus there is

little reason to suspect that Tacitus drew on his knowledge of

the Roman cult in his description of the Germanic Earth-Mother.

Tacitus describes the goddess in question as Terra Mater, not

Magna Mater. The Romans knew a Tellus or Terra Mater, who had a

different ceremony than the one attributed to Nerthus; cattle

were sacrificed to her on the 14th of April.

The worship of Cybele, the great mother of the gods, spread from

its chief sanctuary, Pessinus in Phrygia, to Greece by the early

fourth century and then on to Egypt and Italy. Heeding the

counsel of the Sibylline oracle concerning the threat of foreign

invaders, the Roman senate brought her worship to Rome in 204 BC

as the first officially sanctioned Eastern cult. Lucretius

provides one of the best descriptions of her festival,

considered decadent even by Roman standards, as it was

celebrated around the time of Julius Caesar.

In one telling of her story, the goddess was born a

hermaphrodite and was castrated at birth, leaving her female.

Attis, her consort, was the child of a nymph, impregnated by the

goddess’ discarded member. Cybele fell in love with Attis, but

grew jealous of him after he was unfaithful to her and so drove

him insane. He died from blood-loss after castrating himself.

This myth was reenacted during the festival. In her train, men,

known as Galli, castrated themselves in devotion to her,

following the example of Attis. Since this practice was outlawed

among the Romans, the Galli were all recruited from outside of

Rome. Once a year, decked out in their exotic feminine garments,

long hair and amulets, these self-mutilated eunuchs were allowed

to parade a statue of the goddess, seated in a chariot pulled by

wild lions, through the streets accompanied by the clatter of

cymbals and the sounds of tambourines. Gathered spectators threw

flower petals and coins before them. Bulls were ritually

slaughtered at her increasingly elaborate feasts.

During the rest of the year, the Senate confined the Galli to an

enclosed sanctuary and declared that no citizen had the right to

enter the annexes occupied by them or take part in their

frenzied orgies. In detail, this cult is quite unlike the

peaceful public procession of Nerthus, in which all iron objects

were locked away.

Instead of wild lions, her car was drawn by domestic cattle.

A single priest, rather than a motley crew, attended her and

only he was allowed to touch her sacred vehicle.

Although some scholars have pointed out possible foreign

models for Tacitus’ account of the Nerthus cult, it is more

probable that he based his account on native Scandinavian

tradition.

A divinity in a wagon is well-known in Germanic lore, thus

there is little need to speculate that Tacitus borrowed the

idea from Roman sources. According to Snorri’s Edda, Thor

drives a wagon drawn by goats, Freyr arrives at Baldur’s

funeral in a cart led by a boar, and Freyja rides in a car

pulled by cats. Njörd too is known as ‘god of the wagon’ in

a skaldic strophe cited in the primary manuscript of

Snorri’s Edda; where other manuscripts have Vana guð (‘god

of the Vanir’), Codex Regius has vagna guð.

The Big Dipper (Ursa Major) was commonly known as the Wain

or wagon. In skaldic poetry, Odin is known as runni vagna,

"mover of wagons"; vinr vagna, "friend of wagons";

vári

vagna "protector of wagons"; and valdr vagnbrautar, "ruler

of the wagon-road.” The sky itself, home of the gods, is

known as “the land of wagons (land vagna),” indicating that

the constellations were imagined as the gods circling the

heavens in their cars.

Other Germanic literary sources also support the procession

of an idol in a wagon among the northern European tribes. In

the latter half of the fourth century, the Church historian

Sozomen (c. 400–450 AD), writing of the dangers that beset

Ulphilas [Wulfias] among the heathen Goths, recounts how

Athanaric, chieftain of the Thervingians, appointed Winguric

(Wingureiks), a goði, to eradicate the Christian faith from

the land. He placed a xoanon (wooden idol) in an armamaxa

(covered carriage) and ordered it conveyed to the homes of

those suspected of practicing Christianity. If they refused

to fall down and sacrifice (evidently to the deity

represented by the statue), their tents were set ablaze.

Sozomen says:

“[Ulphilas] exposed himself

to innumerable perils in defense of the faith,

during the period that the aforesaid barbarians were

abandoned to paganism. He taught them the use of

letters, and translated the sacred scriptures into

their own language. …Athanaric resented the change

in religion that had been effected by Ulphilas; and

irritated because his subjects had abandoned the

superstition of their fathers, he imposed cruel

punishments on many individuals; some he put to

death after they had been dragged before tribunals

and had nobly confessed the faith, and others were

slain without being permitted to utter a single word

in their own defense. It is said that the officers

appointed by Athanaric to execute his cruel

mandates, caused a statue to be constructed, which

they placed on a chariot, and had it conveyed to the

tents of those who were suspected of having embraced

Christianity, and who were therefore commanded to

worship the statue and offer sacrifice: if they

refused to do so, they were burnt alive in their

tents. But I have heard that an outrage of still

greater atrocity was perpetrated at this period.

Men, women, and children, who were compelled to

offer sacrifice, fled from their tents and sought

refuge in a church, whither also they carried the

infants at the breast; the pagans set fire to the

church and consumed it, with all who were therein.”[16]

|

In Crimea, Winguric paraded the idol

before a tent used by Christians for their church service.

Those who honored the idol were spared, and the rest were

burned alive in their place of worship around the year 375

AD. A total of 308 people died in the fire, of which

twenty-one are known by name, written with multiple variants

in manuscript. A woman called Baren or Beride, also recorded

as Larisa, led the congregation in a hymn as the fire

consumed them. The so-called “26 Gothic Martyrs” linked to

this incident are commemorated on March 26 in the Christian

Orthodox calendar and on October 29 in the Gothic calendar

fragment, "in remembrance of the martyrs who with Werekas

the priest and Batwin the bilaif (minister?) were burned in

a crowded church among the Goths," gaminþi marwtre þize bi

Werekan papan jah Batwin bilaif aikklesjons fullaizos ana

Gutþiudai gabrannidai.[17]

It is noteworthy that Athanaric did not persecute Christians

in general, but primarily members of his own community who

had converted. Since the purpose of the procession seems to

be to promote prosperity, Carla O'Harris has suggested that

Anthanaric's true motivation in persecuting the coverts may

have been their unwillingness to participate in the

time-honored rituals that would insure the well-being of the

land, and therefore the community at large. His chosen means

of execution, death by fire, may indicate that Athanaric saw

the Christians as practitioners of witchcraft, whose

religious rites would offend the gods and thereby blight the

land.

Footnotes:

[16]

Historia Ecclesiastica VI, 37, translated by Edward Walford as

The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen (1855), pp. 306-7.

[17]

George W. S. Friedrichsen, 'Notes on the Gothic Calendar (Cod.

Ambros. A)’, Modern Language Review 22 (1927); The ‘twenty-six’

martyrs include the twenty-one who are named, Batwin’s four

children, and an anonymous man who ran up to confess his faith

as the tent began to burn.

|

THE GOD SVETOVID (SVANTO-VITH)

This evidence for this idol is a

passage in Book XIV of Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta

Danorum ("Danish History") written before 1220 AD.

There he describes a statue of Suanto-Vitus ("Saint

Vitus") in the following manner:

"[Waldemar I and Absalon lay siege to

Arkon in Rügen, a city on a ness with precipice

walls.]

"On a level in the midst of the city was to be seen

a wooden temple of most graceful workmanship, held

in honour not only for the splendour of its

ornament, but for the divinity of an image set up

within it. The outside of the building was bright

with careful graving [or

painting], whereon sundry shape were rudely and

uncouthly pictured. There was but one gate for

entrance. The shrine itself was shut in a double row

of enclosures, the outer whereof was made of walls

and covered with a red summit; while the inner one

rested on four pillars, and instead of having walls

was gorgeous with hangings, not communicating with

the outer save for the roof and a few beams.

In the temple stood a huge image, far overtopping

all human stature, marvellous for its four heads and

four necks, two facing the breast and two the back.

Moreover, of those in front as well as of those

behind, one looked leftwards and the other

rightwards. The beards were figured as shaven and

the hair as clipped; the skilled workman might be

thought to have copied the fashion of the Rügeners

in the dressing of the heads. In the right hand it

held a horn wrought of divers metals, which the

priest, who was versed in

its rites, used to fill every year with new wine, in order to

foresee the crops of the next season from the

disposition of the liquor. In the left there was a

representation of a

bow,

the arm being drawn back to the side. A tunic was

figured reaching to the shanks, which were made of

different woods, and so secretly joined to the knees

that the place of the join could only be detected by

narrow scrutiny. The feet were seen

close to the earth, their base being hid

underground. Not far off a bridle and saddle and

many emblems of godhead were visible. Men's marvel

at these things was increased by a sword of notable

size, whose scabbard and hilt were not only

excellently graven, but also graced outside with

[mounts or inlaying of] silver.

This image was regularly worshipped in the following

way: Once every year, after harvest, a motley throng

from the whole isle would sacrifice beasts for

peace-offering before the temple of the image, and

keep ceremonial feast. Its priest was conspicuous

for his long beard and hair, beyond the common

fashion of the country. On the day before that on

which he must sacrifice, he used to

sweep

with brooms the shrine, which he had the sole

right of entering. He took heed not to breathe

within the building. As often as he needed to draw

or give breath, he would run out to the door, lest

forsooth the divine presence should be tainted with

human breath. On the morrow, the people being at

watch before the doors, he took the cup from the

image, and looked at it narrowly; if any of the

liquor put in had gone away he thought that this

pointed to a scanty harvest for next year. When he

had noted this he bade them keep, against the

future, the corn which they had. If he saw no

lessening in its usual fulness, he foretold fertile

crops. So, according to this omen, he told them to

use the harvest of the present year now thriftily,

now generously. Then he poured out the old wine as a

libation at the feet of the image, and filled the

empty cup with fresh; and, feigning the part of a

cupbearer, he adored the statue, and in a regular form of address prayed for good increase of

wealth and conquests for himself, his country and

its people. This done, he put the cup to his lips,

and drank it up over-fast at an unbroken draught;

refilling it then with wine, he put it back in the

hand of the statue. Mead-cakes were also placed for

offering, round in shape and great, almost up to the

height of a man's stature. The priest used to put

this between himself and the people, and ask,

Whether the men of Rügen could see him? By this

request he prayed not for the doom of his people or

himself, but for increase of the coming crops. Then

he greeted the crowd in the name of the image, and

bade them prolong their worship of the god with

diligent sacrificing, promising them sure rewards of

their tillage, and victory by sea and land. ... [The

people keep orgy the rest of the day to please the

god.]

... Each male and female hung a coin every year as a

gift in worship of the image. It was also allotted a

third of the spoil and plunder, as though these had

been got and won by its protection. This god also

had 300 horses appointed to it, and as many

men-at-arms riding them, all of whose gains, either

by arms or theft, were put in the care of the

priest. Out of these spoils he wrought sundry

emblems and temple-ornaments which he consigned to

locked coffers containing store of money and piles

of time-eaten purple. Here, too, was to be seen a

mass of public and private gifts, the contributions

of anxious suppplicants for blessings. This statue

was worshipped with the tributes of all Sclavonia,

and neighbouring kings did not fail to honour its

sacrifice with gifts. ...[Even Sweyn gave a wrought

cup, and there were smaller shrines. ]

...Also it possessed a special white horse, the hairs of whose mane and

tail it was thought impious to pluck, and which only

the priest had the privilege of feeding and riding,

lest the use of the divine beast might become common

and therefore cheap. On this horse, in the belief of

Rügen, Suanto-Vitus —so the image was called—rode to

war against the foes of his religion. The chief

proof was that the horse when stabled at night was

commonly found in the morning, bespattered with mire

and sweat, as though he had come from exercise and

travelled leagues. Omens also where taken by this

horse, thus: When war was determined against any

district, the servants set out three rows of spears,

two joined crosswise, each row being planted point

downwards in the earth; the rows an equal distance

apart. When it was time to make the expedition,

after a solemn prayer, the horse was led in harness

out of the porch by the priest.

If

he crossed the rows with the right foot

before the left it was taken as a lucky omen of

warfare; if he put the left first, so much as once,

the plan of attacking that district was dropped;

neither was any voyage finally fixed, until three

paces in succession of the fortunate manner of

walking were observed. Also folk faring out on

sundry businesses took an omen concerning their

wishes from their first meeting with the beast. Was

the omen happy, they blithely went on with their

journey; was it baleful, they turned and went home.

Nor were

these people ignorant of the use of lots. Three bits

of wood black on one side, white on the other, were

cast into the lap. Fair, meant good luck; dusky,

ill.

Neither were their women free from this sort of

knowledge, for they would sit by the hearth and draw

random lines in the ashes without counting. If these

when counted were even, they were thought to bode

success; if odd, ill-fortune. [The king goes to

attack the town and efface profane rites. His men

make works, but he says these are needless] because

the Rügeners had once been taken by Karl Cæsar , and

bidden to honour with tribute Saint Vitus of Corvey,

famous for his sanctified death. But when the

conqueror died they wished to retain freedom, and

exchanged slavery for superstition, putting up an

image at home to which they gave the name of the

holy Vitus, and, scorning the people of Corvey, they

proceeded to transfer the tribute to its worship,

saying that they were content with their own Vitus,

and need not serve a strange one. [Vitus would come

and avenge himself, so the king prophesies; the

siege is related; the people trust their defences,

and guard] the tower over the gate only with emblems

and standards. Among these was Stanitia

[margin,

Stuatira], notable for size and hue, which

received as much adoration from the Rügeners as

almost all the gods together; for, shielded by her,

they took leave to assail the laws of God and man,

counting nothing unlawful which they liked. ... [the

town is taken and fired].

[The image could not be prized up without iron

tools. Esbern and Snio cut it down]. The image fell

to the ground with a crash. Much purple hung round

the temple; it was gorgeous, but so rotten with

decay that it could not bear the touch. There were

also the horns of woodland beasts, marvellous in

themselves and for their workmanship. A demon in the

form of a dusky animal was seen to quit the inner

part and suddenly vanish from the sight of the

bystanders. [The image of Suanto- Vitus is then

chopped into firewood.]"

[Asalon goes against the Karentines; takes the town,

and comes upon three temples of a similar kind to

that at Arkon.] The greater temple was situated in

the midst of its own ante-chamber, but both were

enclosed with purple [hangings] instead of walls,

the summit of the roof being propped merely on

pillars. So the servants, tearing down the rear of

the ante- chamber, at last stretched out their hands

to the inmost veil of the temple. This was removed,

and an oaken image which they called Rugie-Vitus

[Rügen's Vitus] was exposed on every side amid

mockery at its hideousness. For the swallows had

built their nests beneath its features, and had

piled a heap [of droppings on its breast. The god

was only fit to have his effigy hideously befouled

by birds. Also in its head were set seven faces,

after human likenesses, all covered under a single

poll, and the workman had also bound by its side in

a single belt seven real swords with their

scabbards. The eighth it held in its hand drawn;

this was fitted in the wrist and fixed very fast

with an iron nail, and the hand must be cut off

before it could be wrenched away: which led to the

image being mutilated. Its thickness was beyond that

of a human body, but it was so long that Absalon,

standing a-tip-toe, could scarce reach its chin with

the little axe he was wont to carry in his hand. The

people had believed this god to preside over wars,

as if it had the power of Mars. Nothing in this

image pleased the eye; its features were hideous

with uncouth gravings [or painting]. [It is cut

down, and its own people spurn it and are converted.

The assailants go on] to the image of Pore-Vitus,

which was worshipped in the next town. This was also

five-headed, but represented without weapons. On

this being cut down they go to the temple of

Porenutius. This statue representing four faces had

the fifth inserted in its bosom; its left hand

touched the brow, and its right the chin [It was

destroyed.]

—Oliver Elton Translation (1894)

|

|

THE GOD FLYNT

Conrad Bote of Brunswick in

his Saxon Chronicle (1492) says the deity of Death was

named Flins; and on the Spree, near Budissin, the

place where the idol was fixed still retains the

name of Flinstein, and is lithographed in

Preusker's Blicke, &c. (below), with the

spot more particularly designated where his figure

of solid gold is said to have stood, and to have

been thrown thence into the Spree below when the

Germans attempted to destroy this Wendic deity. Just

below the place is a cavern, said to extend to the

neighbouring village, with a room full of barrels of

gold. Independently of such general reports of

immense riches where heathen temples are believed to

have existed (and some numerous so-called

ring-monies at Carnac and elsewhere, with torques,

&c., would seem in some measure to countenance the

idea), more sure traces of a religious Pagan station

exists here in the tradition that it was a customary

penance to traverse from this place to the altar of

Zernibog, or Tchernebog, on the knees.

This deity has been alternately called Flins and

Flint or Flynt. Richard Verstegan, writing in Restitution

of Decayed Intelligence in Antiquities (1605),

describes the god pictured here in this manner:

"They adored also the Idoll FLYNT, who had that name

for his being set upon a great Flint stone. This

idoll was made like the Image of death, and naked,

save onely a sheete about him. In his right hand he

held a torch, or as they termed it, a fire blase. On

his head a Lyon rested his two fore-feet, standing

with the one of his hinder feet upon his left

shoulder, and with the other in his hand; which to

support, he lifted up as high as his shoulder."

On page 122, Arnkiel speaks of the god Flins who stands

on a flintstone as a Wendish god, citing his source as

Vetus Chron. Saxon a Pomario editum p. 245. Also

Schedius Syng. 3,

De Diis Germanis, ch. 7. And refers to his

worship by a Vandal king Vißlou (?) in the year 90 in

Swabia near Pommern and Brandenberg.

|

THE

GODS

RADEGAST, PRONE and SIWE

This image is clearly based on the one below from Bote's Saxon

Chronicle. |

| |

|

Conrad Bote of Brunswick's Chronicles of the

Saxons, 1492

On page 119, Arnkiel speaks of the Vandal

goddess Siva or Siwe of Polaber or Raßberg; and

Ridegast, the god of Obotrist or Meckelberg,

citing his

sources as Helmoldus Book I, ch. 53

and Albert Crantz, Wandalia Book 37. The

picture and the information given by Arnkeil

both appear to be drawn from Bote's Chronicle.

The principal works upon Lower

Saxony in the fourteenth century are

the Chronicle of Hermann Cornerus of Lübeck; in

the fifteenth, Albert Crantz's Saxonia and Vandalia,

as well as Conrad Bote of Brunswick's

Chronicle of the Saxons. The

direct Nether-Dutch

of Bote's Picture Chronicle,

printed at Mentz in 1492 under the title

Cronecken der Sassen [Saxon Chronicle], is

amply illustrated with woodcuts, including

several of heathen gods.

RADEGAST, “Dear

Guest” or “Good Guest”, is mentioned by Adam of

Bremen in his 10th century Gesta

Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum as the

deity worshipped by the West Slavic Lutician

tribes in the city of Radgosc. In

his Chronica Slavorum, Helmold designated

Radegast as a Lutician god. However, in

his Chronicon, Thietmar of Merseburg wrote that

the pagan Luticians worshipped many gods,

in their holy city of Radegast, the most

important of which was named Zuarasici,

identified as Svarog. Johannes Scotus, Bishop

of Mecklenburg, was sacrificed to that god on 10

November 1066, during a Wendish rebellion

against Christianity according to Adam of

Bremen.

Mistevoi, the valiant prince of the Obotrites,

served under the banner of Otto II in Italy. On

his return home, he pursued the hand of the

sister of the Duke of Saxony. Upon being

insulted by a jealous rival, Dietrich of

Brandenburg, who called him a dog of a Slav, not

worthy to mate with a Christian bride, Mistevoi replied,

"If we Slavs be dogs, we shall show you we

bite." The pagan Slavs, ever ripe for revolt,

obeyed his call. An oath of eternal enmity

against the Germans and the priests was sworn

before their idol, Radegast, and they rose

suddenly in open rebellion (983 AD),

assassinating all who fell into their hands,

razing churches to the ground, and completely

destroying the cities of Hamburg, Oldenburg,

Mecklenburg, Brandenburg and Havelburg. The

heathen party, headed by Plasso, rose up and

extirpated Christianity, sacrificing John,

bishop of Mecklenburg, to their gods; stoning to

death St. Answar, Abbot of Ratzeburg, and

twenty-eight monks; assassinating Gotteschalk in

Lenzen at the foot of the altar; butchering Eppo

the priest as he was offering the Holy Sacrifice

upon the altar itself, and slaughtered the

rest of the Christians who were left in

the sanctuary. Altogether, sixty priests were flayed

alive. The heathens were, however, decisively

beaten back in a pitched battle at Tangermünde.

Prono, an idol of the ancient Slavonians

worshipped at Altenburg (Oldenburg) in Germany,

was a statue erected on a column, holding a

ploughshare in one hand , and in the other a

spear and a standard. Its head was crowned, its

ears prominent, and from one of its feet was

suspended a little bell.

The god Prone, also Prove,

is cited as appearing in Albert Crantz's Wandalia ch.

37; Schedius

De Diis Germanis; Conf. Bangeretti notas in

Helmoldus

Book 1, chapter 84.

Helmold, writing of the pagan revival among the

Wends in 1134, refers to "Prove deus

Aldenburgensis terrae," Prove, God of the

Oldenburg territory.

Bangert, in his notes to Helmold, notes the

variant spelling Prono, which has led some scholars to

associate the name with Perun. [Bangeretti notas

in Helmoldus

Book 1, chapter 84.

]

Helmold I, 84 “The Slavs have multiple modes of

idolatry, as not all of them practice the same

superstitions. Some erect strange statues in

temples, as for instance the effigy in Plön

which is named which is named Podaga,

other deities inhabit forests and groves, for

example Prove, the god of Oldenburg. Those are

not represented in any effigies. But many gods

are carved with two, three or even more heads.”

Helmold von Bosau describes the holy grove

of the god Prove, which grew a short

distance from the city of Starigard (modern

Oldenburg, Lower Saxony, Germany). Assemblies

were held and princely judgements pronounced

there. A cult centre, with another

sanctuary containing an idol of Prove, was located in

the princely stronghold at Starigard of the

Wagrians. The grove, which consisted of ancient

oaks, enclosed an atrium, surrounded by an

ornamental fence with two gates.

In the regions of present day northern Germany

and Poland, the Slavs clung fiercely to their

heathen religion until their final conversion,

accompanied by a savage destruction of their

idols in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Presbyter Helmold provides a contemporary

account of how he helped destroy one such

"profane place" near Oldenburg in 1156. Led by

the bishop, he writes, "we entered the atrium,

leapt the fence around the sacred trees, and

having set fire to a pile of wood, made a

funeral pyre, not without fear, lest we be

overwhelmed by a tumult of the populace."

Ceroid, Christian bishop of Altenburg, destroyed

this idol with his own hand, and cut down the

grove in which it was worshipped.

|

|

FOSTA AND WEDA

Gods of the Frisians

| On page 112,

Arnkiel states that the Frisans worshipped the

gods Foseta or Fosta and Weda when the Romans

came as described in the 8th chapter of

Book I of Walter's "Chron.

Fres," (Chapter 8 begins on p. 118). He goes

on to say that Mr. Heinrich Walter states that

the Frisians (Freschen) had four gods Phoseta or

Fosta, Freda, Meda and Weda. According to

p. 113, these gods appear in the "Nord-Freschen

Chronick". |

|

Nordfresische Chronik, M. Anton

Heimreichs, Chapter 8 (translated by Peter

Kröger):

"From the North

Frisians idolatry and funerals The North Frisian

have been at their first arrival pagan tribes,

such as the other tribes at the same time,

except Carolum M., lived in great idolatry.

Initially they did not build temples for their

gods or created depictions, as they considered

that they could not lock them into temples or

houses or depict them as human figures.

"For this reason they consecrated the

green trees with many branches and twigs and

worshiped there their gods. Later, as they dealt

with the Romans, they learned from them to erect

temples and depictions. As the maps show there

was at Everschup near Garding a Templum Martis,

in Uthholm south of Süderbever Templum Medae and

in Eiderstedt near Cating Templum Wodae; in

Nordstrand at the Süderog Templum Veneris and

north of the Hoge Templum Saturni, but in

Norgößharde Templum Martis, namely at the place

where the church of Borkum stands (I was told

that at this place in former times a pagan

church stood) and in Osterharde on (the island)

Amrum Templum Saturni and Phostae and on (the

island) Sylt near Niblum Templum Veneris such as

at the same place Templum Phostae, Wodae, Martis

and Saturni stood.

"The Frisians especially honored and

worshiped primarily four idols, with the names

Phoseta or Fosta, Freda, Meda and Woda. Of

these, Meda and Phoseta had in his right hand

some arrows, and in the left hand a sheaf of

corn; but Freda and Woda had on their breast a

shield, a helmet on the head, at arms and legs

they were naked, and they had wings on their

back; leading to the conclusion that the former

have been worshiped in agriculture, but the

others were worshipped during wars. And I have

seen on the 12 June Anno 1650 depictions of

Phostä and Wödä seen next to a large horn,

whereby the people have been summoned for

idolatry in S. Mary's Church at Utrecht itself.

But among the idols Phoseta has been the most

noble one, who has been the Vesta of the mother

of Saturni who was named so as she decorated the

earth with flowers herbs and fruits, and which

has been the most honored in all Frisian

countries, of which also Heiligland (‘Holy

Land’) (which is also called Farrö or Farria

Insula) formerly Fosetis, Fostis and Phosteland

was called; and Heiligland, because there from

time immemorial have been performed many

pilgrimages to the forests and the pagan temples

of Phostä or Vestae.

"On their feast

days they danced and jumped after finishing of

idolatry and they worshiped their idol Kom, of

which Mr. Richardus Petri sent me messages from

the Föhringer country where he raised the idea

that the same is Deus Komus comessationum

nocturnarumque saltationum praeses, which

is a God of eating and night dances. Such

pagance as Bonifacius called it or pagan customs

have not be abolished by the church easily,

because not only the behaviour at these places

was kept by the papacy that on Sundays and

especially on the high festivals there was

dancing, as Mr. Richardus Petri told me, that

old people still could tell that at their time

many young women on Westerlandföhr, at the

Westerkirchhofpforten danced into the new year

and on the afternoon after the church service."

|

The following map

showing the temple of "Fostæ and Phoseta c. 768"

(upper left) was first printed in

Travels in Various Countries of Europe,

Asia and Africa. 3. Ed by

Daniel Edward Clarke (1819).

|

|

|

Derivative Works

|

1728 Elias

Schedius

De Diis Germanis

1826 Christian August Vulpius

Handwörterbuch der Mythologie

1837 Leopold Ziegelhauser

Allgemeine Populäre Götterlehre

|

|

|

|