The First English Translation of

GYLFAGINNING

An Introduction

Published in

OR, A DESCRIPTION OF THE

Manners, Customs, Religion and Laws

OF THE ANCIENT DANES

And other Northern Nations;

Including those of

OUR OWN SAXON ANCESTORS. WITH

A Translation of the EDDA,

or System of RUNIC MYTHOLOGY,

AND OTHER PIECES,

From the Ancient Islandic Tongue.

In TWO VOLUMES.

Translated from Mons. Mallet’s Introduction a l'Histoire de Dannemarc, &c.

With Additional Notes By The English Translator,

And Goranson's Latin Version Of The EDDA.

Translated and Annotated by Bishop Thomas Percy

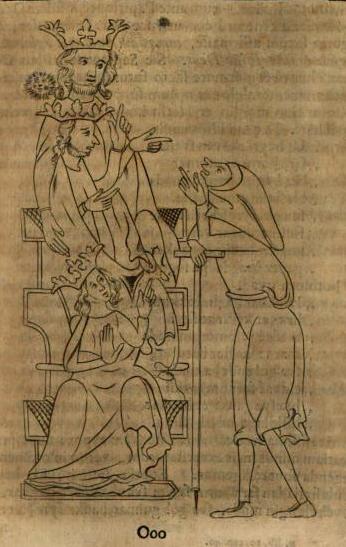

An illustration in a MSS of Snorri's Edda reproduced in

Thomas Bartholin's Causæ Contempt a Danis Mortis. pag. 473

[HOME]

|

THE AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME THE SECOND. |

||

|

I know not, whether among the multitude of interesting objects which history offers to our reflection, there are anymore worthy to engage our thoughts, than the different Religions which have appeared with splendour in the world. It is on this stage, if I may be allowed the expression, that men are represented, as they really are; that their characters are distinctly marked and truly exhibited. Here they display all the foibles, the passions and wants of the heart; the resources, the powers and the imperfections of the mind. It is only by studying the different Religions that we become sensible how far our natures are capable of being debased by prejudices, or elevated, even above themselves, by found and solid principles. If the human heart is a profound abyss, the Religions that have prevailed in the world have brought to light its most hidden secrets: They alone have imprinted on the heart all the forms it is capable of receiving. They triumph over everything that has been deemed most essential to our nature. In short it has been owing to them that man has been, either a Brute or an Angel. This is not all the advantage of this study: Without it our knowledge of mankind must be extremely superficial. Who knows not the influence which Religion has on manners and laws? Intimately blended, as it were, with the original formation of different nations, it directs and governs all their thoughts and actions. In one place we see it enforcing and supporting despotism; in another restraining it: It has constituted the very soul and spirit of more than one republic. Conquerors have frequently been unable to depress it, even by force; and it is generally either the soul to animate or the arm to execute the operations of politics. Religion acts by such pressing motives, and speaks so strongly to mens most important and dearest interests, that where it happens not to be analagous to the national character of the people who have, adopted it will soon give them a character analogous to its own: One of these two forces must unavoidably triumph over the other, and become both of them blended and combined together; as two rivers when united, form a common stream, which rapidly bears down all opposition. But in this multitude of Religions, all are not equally worthy of our research. There are, among some barbarous nations, Creeds without ideas, and practices without any object; these have at first been dictated by fear, and, afterward continued by mere mechanical habit. A single glance of the eye thrown upon such Religions as these, is sufficient to show us all their relations and dependencies. The thinking part of mankind, must have objects more relative to themselves; they will never put themselves in the place of a Samoiede or an Algonquin: Nor bestow much attention upon the wild and unmeaning superstitions of barbarians, so little known and unconnected with themselves. But as for these parts of the world, which we ourselves inhabit, or have under our own immediate view; to know something of the Religions which once prevailed here and influenced the fate of these countries, cannot surely be deemed uninteresting or unimportant. Two* principal

Religions for many ages divided between them all these countries

which are now blessed with Christianity: Can we comprehend the

obligations we owe to the Christian Religion, if we are ignorant

from what principles and from what opinions it has delivered us? Nevertheless that Religion only extended itself in Europe over Greece and Italy. How indeed could it take root among the conquered nations, who hated the Gods of Rome both as foreign Deities, and as the Gods of their masters? That Religion then so well known among us, that even our children study its principal tenets, was confined within very narrow bounds, while the major part of Gaul, of Britain, Germany and Scandinavia uniformly cultivated another very different, from time immemorial. The Europeans may

reasonably call this Celtic* worship, the Religion of their

fathers; Italy itself having received into her bosom more than

one conquering nation who professed it. This is the Religion

'which they would probably still have cultivated had they been

left for ever to themselves, and continued plunged in their

original darkness: This is the Religion, which (if I may be

allowed to say so) our climate, our constitutions, our very

wants are adapted to and inspire: For who can deny, but that in

the false religions, there are a thousand things relative to

these different objects? It is, in short, this Religion, of

which Christianity (though after a long conflict, it triumphed

over it) could never totally eradicate the vestiges.” [Thus far our ingenious Author, who having been led by Pelloutier and Keyslar into that fundamental error (which has been the stumbling-block of modern antiquaries) viz. That the Celts and Goths were the same people, supposes that the Druidical system of the Celtic nations, was uniformly the same with the Polytheism of the nations of Gothic Race: Than which there cannot be a greater mistake in itself, nor a greater source of confusion in all our researches into the antiquities of the European nations. The first inhabitants of Gaul and Britain, being of Celtic Race, followed the Druidical superstitions. The ancient Germans, Scandinavians, &c. being of Gothic Race, professed that system of Polytheism, afterwards delivered in the EDDA: And the Franks and Saxons, who afterwards settled in Gaul and Britain, being of GoThic Race, introduced the Polytheism of their own nation, which was in general the fame with What prevailed among all the other Gothic or TEUTONIC people, viz. the Germans, Scandinavians, &c. After all it is to be

observed, in favour of our Author's general course of reasoning,

that in Gaul and Britain, and in many other countries,

innumerable reliques both of the Celtic ‘and Gothic’

superstitions, are still discernable among the common people; as

the present inhabitants of those countries derive their descent

equally from the Goths and Celts, who at different times were

masters of these kingdoms, and whose descendants are now so

blended and mingled together.] T. But doth not a knowledge of the Religions professed by the ancient Celtic ‘and Gothic’ nations lead to discoveries of the fame kind, and perhaps to others still more interesting? One generation imitates the preceding; the sons inherit their fathers sentiments, and whatever change time may effect, the manners of a nation always retain traces of the opinions professed by its first founders. Most of the present nations of Europe derive their origin either from the Celts or Goths, and the sequel of this work will show, perhaps, that their opinions, however obsolete, still subsist in the effects which they have produced. May not we esteem of this kind (for example) that love and admiration for the profession of arms, which was carried among us even to fanaticism, and which for many ages incited the Europeans, mad by system and fierce through a point of honour, to fight, with no other view, but merely for the sake of fighting? May not we refer to this source, that remarkable attention and respect which the nations of Europe have paid to the fair sex, by which they have been so long the arbiters of glorious actions, the aim and the reward of great exploits, and that they yet enjoy a thousand advantages which everywhere else are reserved for the men? Can we not explain from these Celtic ‘and Gothic’ Religions, how, to the astonishment of posterity, judiciary combats and ordeal proofs were admitted by the legislature of all Europe; and how, even to the present time, the people are still infatuated with a belief of the power of Magicians, Witches, Spirits, and Genii, concealed under the earth or in the waters, &c.? In fine, do we not discover in these religious opinions, that source of the marvellous with which our ancestors filled their Romances, a system of wonders unknown to the ancient Classics, and but little investigated even to this day; wherein we see Dwarfs and Giants, Fairies and Demons acting and directing all the machinery with the most regular conformity to certain characters which they always sustain. What reason then can be assigned, why the study of these ancient Celtic ‘and Gothic’ Religions hath been so much neglected? One may, I fancy, be immediately found in the idea conceived of the Celts and Goths in general, and especially of the Germans and Scandinavians. They are indiscriminately mentioned under the title of Barbarians, and this word, once spoken, is, believed to include the whole that can be said on the subject. There cannot be a more commodious method of dispensing with a study, which is not only considered as not very agreeable, but also as affording but little satisfaction. Were this term to be admitted in its strictest sense, it should not even then excuse our intire disregard of a people, whose exploits and institutions make so considerable a figure in our history. But ought they, after all, to be represented as a troop of savages, barely of a human form, ravaging and destroying by mere brutal instinct, and totally devoid of all notions of religion, policy, virtue and decorum? Is this the idea Tacitus gives us of them, who, though born and educated in ancient Rome, professed that in many things ancient Germany was the object of his admiration and envy. I will not deny but that they were very far from possessing that politeness, knowledge and taste which excite us to search with an earnestness almost childish, amid the wrecks, of what by way of excellence, we call Antiquity; but allowing this its full value, must we carry it so high, as to refuse to bestow the least attention on another kind of Antiquities; which may, if you please, be called Barbarous, but to which our manners, laws and governments perpetually refer? The study of the

ancient Celtic ‘and Gothic’ Religions hath not only appeared

devoid of blossoms and of fruits; it hath been supposed to be

replete with difficulties of every kind. The Celtic Religion, it

is well known, forbad its followers to divulge its mysteries in

writing,* and this prohibition, dictated either by ignorance or

by idleness, has but too well taken effect. The glimmering rays

faintly scattered among the writings of the Greeks and Romans,

have been believed to be the sole guides in this enquiry, and

from thence naturally arose a distaste towards it. Indeed, to

Say nothing of the difficulty of uniting, correcting and

reconciling the different passages of ancient authors, it is

well known that mankind are in no instance so little inclined to

do justice to one another, as in what regards any difference of

Religion. And what satisfaction can a lover of truth find in a

course of reading wherein ignorance and partiality appear in

every line? Readers who require solid information and exact

ideas, will meet with little satisfaction from these Greek and

Roman authors, however celebrated. Divers circumstances may

create an allowed prejudice against them. We find that those

nations who pique themselves most 'on their knowledge and

politeness, are generally those, who entertain the falsest and

most injurious notions of foreigners. Dazzled with their own

splendor, and totally taken up with self-contemplation, they

easily persuade themselves, that they are the only source of

everything good and great. To this we may attribute that habit

of referring everything to their own manners and customs which

anciently characterized the Greeks and Romans, and caused them

to find Mercury, Mars and Pluto, their own Deities and their own

doctrines, among a people who frequently had never heard them

mentioned. It is only from the mouths of its own professors that we can acquire a just knowledge of any Religion. All other interpreters are here unfaithful; sometimes condemning and aspersing what they explain; and often venturing to explain what they do not understand. They may, it is true give a clear account of some simple dogmas; but a religion is chiefly characterized and distinguished by the sentiments it inspires; and can these sentiments be truly represented by a third person, who has never felt the force of them? In order then to draw from their present obscurity the ancient Celtic ‘and Gothic’ Religions, which are now as unknown, as they were formerly extensively received) We must endeavour (if we can) to raise up before us those ancient Poets who were the Theologues of our forefathers: We must consult them in person, and hear them (as it were) in the coverts of their dark umbrageous forests, chant forth those sacred and mysterious hymns, in which they comprehended the whole system of their Religion and Morality. Nothing of moment would then evade our search; such informations as these would diffuse real light over the mind: The warmth, the stile and tone of their discourses, in short, everything would then concur to explain their* meaning, to put us in the place of the authors themselves, and to make us enter into their own sentiments and notions. But why do we form vain

and idle wishes? Instead of meeting with those poems themselves,

we only find lamentations for their loss. Of all those verses of

the ancient Druids, which their youths frequently employed

twenty years to learn*, we cannot now recover a single fragment,

or the slightest relique. The devastations of time, and a false

zeal, have been equally fatal to them in Spain, France, Germany

and England. This is granted, but should we not then rather look

for their monuments in countries, later converted to

Christianity? If the poems, of which we speak, have been ever

committed to writing, shall we not more probably find them

preserved in the north, than where they must have struggled for

five or six centuries more against the attacks of time and

superstition? This is no conjecture; it is what has really

happened. We actually possess some of these Odes,** which are so

much regretted, and a very large work extracted from a multitude

of others. This extract was compiled many centuries ago by an

author well known, and who was near the fountain head; it is

written, in a language not unintelligible, and is preserved in a

great number of manuscripts which carry incontestible characters

of antiquity. This extract is the book called the EDDA; the only

monument of its kind; singular in its contents, and so adapted

to throw light on the history of our ancient opinions and

manners, that it is amazing it should remain so long unknown

beyond the confines of Scandinavia.

** Here again our

author falls into the unfortunate mistake of confounding the

Celtic ‘and Gothic’ Antiquities. The Celtic Odes of the Druids

are forever lost; but we happily possess the RuNic Songs of the

Gothic Scalds: These however have nothing in common with the

Druid Odes, nor contribute to throw the least light on the

Druidical Religion of the Celtic nations: But then they are full

as valuable, for they unfold the whole Pagan system of our

Gothic ancestors; in the discovery of which we are no less

interested in than that of the other'. T. I trusted we should find the causes of this their love of poetry, in the ruling passion of the ancient Scandinavians for war, in the little use they made of writing, and especially in their peculiar system of Religion. What was at first only conjecture, a later research hath enabled me to discover to have been the real case: And I flatter myself that the perusal of the EDDA will remove every doubt which may at first have been entertained from the novelty and singularity of the facts which I advanced. It now remains for me

to relate in a few words the history of this Book, and to give a

short account of my own labours. I have already hinted that

there have been two EDDAS. The first and most ancient was

compiled by SÆMUND SIGFUSSON, sirnamed the Learned, born in

Iceland about the year 1057. This Author had studied in Germany,

and chiefly at Cologne, along with his countryman Are, sirnamed

also Frode, or the Learned; and who likewise distinguished

himself by his love for the Belle-Lettres.*

SÆMUND was one of the first who ventured to commit to

writing the ancient religious Poetry, which many people still

retained by heart. He seems to have confined, himself to the

meer selecting into one body such of the ancient Poems as

appeared most proper to furnish a sufficient number of poetical

figures and phrases. It is not determined whether this

collection (which, it should seem, was very considerable) is at

present extant, or not: But without engaging in this dispute, it

suffices to say, that Three of the Pieces of which it was

composed, and perhaps those three of the most important, have

come down to us. We shall give a more particular account of

these in the body of this work. **The Reader may see a

literal translation of this Preface prefixed to GORANSON'S Latin

Version, at the end of this Volume: Vid. pag. 275—280. It is

printed in Italics, to distinguish it from the EDDA itself. T. **Vid. Liv. i. T. These doubts being

removed, it only remains to clear up such as may arise

concerning the fidelity of these different translations. I

freely confess my imperfect knowledge of the language in which

the EDDA is written. It is to the modern Danish or Swedish

languages, what the dialect of Ville-hardouin, or the

Sire de Joinville is to modern French.* I should have

been frequently at a loss, if it had not been for the assistance

of Danish and Swedish versions of the EDDA, made by learned men

skilful in the old Icelandic tongue. I have not only consulted

these translations, but by comparing the expressions they employ

with those of the original, I have generally ascertained the

identity of the phrase, and attained to a pretty strong

assurance that the sense of my text hath not escaped me. Where I

suspected my guides, I have carefully consulted those, who have

long made the EDDA, and the language in which it is written,

their peculiar study. I stood particularly in need of this

assistance, to render with exactness the two fragments of the

more ancient EDDA, namely, the Sublime Discourse Of ODIN, and

the Runic Chapter; and here too my labours were more

particularly assisted. This advantage I owe to Mr. Erichsen, a

native of Iceland, who joins to a most extensive knowledge of

the antiquities of his country, a judgment and a politeness not

always united with great erudition. He has enabled me to give a

more faithful translation of those two pieces than is to be met

with in the EDDA of RESENIUS. With regard to the text, RESENIUS hath taken the utmost care to give it correct and genuine. He collated many MSS. of which the major part are still preserved in the royal and university libraries; but what he chiefly made the greatest use of, was a MS. belonging to the King, which is judged to be the most ancient of all, being as old as the thirteenth, or at least the fourteenth century, and still extant. Exclusive of this, we do not find in the edition of Resenius any critical remarks, calculated to elucidate the contents of the EDDA. In truth, the Preface seems intended to make amends for this deficiency, since that alone would fill a volume of the size of this book; but, excepting a very few pages, the whole consists of learned excursions concerning Plato, the best editions of Aristotle, the Nine Sybils, Egyptian Hieroglyphics, &c. From the manuscript

copy of the EDDA preserved in the university library of Upsal

hath been published a few years since, a second edition of that

work. This MS. which I have often had in my possession, seems to

have been of the fourteenth century. It is well preserved,

legible, and very entire. Although this copy contains no

essential difference from that which RESENIUS has followed, it

notwithstanding afforded me assistance in some obscure passages;

for I have not scrupled to add a few words to supply the sense,

or to suppress a few others that seemed devoid of it, when I

could do it upon manuscript authority: and of this I must beg my

readers to take notice, whenever they would compare my version

with the original: for if they judge of it by the text of

Resenius, they will frequently find me faulty, since I had

always an eye to the Upsal MS. of which Mr. Solberg, a young

learned Swede, well versed in these subjects, was so good as to

furnish me with a correct copy. The text of this MS. being now

printed, whoever will be at the trouble, may easily see, that I

have never followed this new light, but when it appeared a surer

guide than RESENIUS. M. GORANSON, a Swede, hath published it

with a Swedish and Latin version, but he has only given us the

first part of the EDDA: Prefixed to which, is a long

Dissertation on the Hyperborean Antiquities; wherein the famous

Rudbeck seems to revive in the person of the Author.* Without doubt, this task should have been assigned to other hands than mine. There are in Denmark many learned men, from whom the public might have expected it, and who would have acquitted themselves much better than I can. I dissemble not, when I avow, that it is not without fear and reluctance, that I have begun and finished this work, under the attentive eyes of so many critical and observing judges: But I flatter myself that the motives which prompted me to the enterprize, will abate some part of their severity. Whatever opinion may be formed of these Fables and of these Poems, it is evident they do honour to the nation that has produced them; they are not void of genius or imagination. Strangers who shall read them, will be obliged to soften some of those dark colours in which they have usually painted our Scandinavian ancestors. Nothing does so much honour to a people as strength of genius and a love of the arts. The rays of Genius which shone forth in the Northern Nations, amid the gloom of the dark ages, are more valuable in the eye of reason, and contribute more to their glory than all those bloody trophies, which they took so much pains to erect. But how can their Poetry produce this effect, if it continues unintelligible to those who wish to be acquainted with it; if no one will translate it into the other languages of Europe? The professed design of this Work required, that the Version should be accompanied by a Commentary. It was necessary to explain some obscure passages, and to point out the use which might be made of others: I could easily have made a parade of much learning in these Notes, by laying under contribution the works of BARTHOLIN, WORMIUS, VERELIUS, AMKIEL, KEYSLAR, SCHUTZE, &c. but I have only borrowed from them what appeared absolutely necessary; well knowing that in the present improved state of the republick of letters, good sense hath banished that vain ostentation of learning, brought together without judgment and without end, which heretofore procured a transitory honour to so many persons laboriously idle. I am no longer afraid of any reproaches on that head: One is not now required to beg the Reader's pardon for presenting him with a small book. But will not some object. To what good purpose can it serve to revive a heap of puerile Fables and Opinions, which time hath so justly devoted to oblivion? Why take so much trouble to dispel the gloom which envelopes the infant state of nations? What have we to do with any but our own cotemporaries? much less with barbarous manners, which have no fort of connection with our own, and which we shall happily never fee revive again? This is the language we now often hear. The major part of mankind, confined in their views, and averse to labour, would fain persuade themselves that whatever they are ignorant of is useless, and that no additions can be made to the stock of knowledge already acquired. But this is a stock which diminishes whenever it ceases to increase. The same reason which prompts us to neglect the acquisition of new knowledge, leads us to forget what we have before attained. The less the mind is accustomed to exercise its faculties, the less it compares objects, and discovers the relation they bear to each other. Thus it loses that strength and accuracy of discernment which are its best preservatives from error. To think of confining our studies to what one may call near necessary truths, is to expose one's self to the danger of being shortly ignorant of those truths themselves. An excess and luxury (as it were) of knowledge, cannot be too great, and is never a doubtful sign of the flourishing state of science. The more it occasions new researches, the more it confirms and matures the preceding ones. We see already, but too plainly, the bad, effects of this spirit of æconomy, which, hurtful to itself, diminishes the present stock of knowledge, by imprudently refusing to extend it. By lopping off the branches, which hasty judgments deem unprofitable, they weaken and impair the trunk itself. But the truth is, it would cost some pains to discover new facts of a different kind from what we are used to; and therefore men chuse to spare themselves the trouble, by continually confining themselves to the old ones. Writers only show us what resembles our own manners. In vain hath nature varied her productions with such infinite diversity. Although a very small movement would procure us a new point of view, we have not, it seems, either leisure or courage to attempt it. We are content to paint the manners of that contracted society in which we live, or perhaps of only a small part of the inhabitants of one single city; and this passes without any opposition for a compleat portrait of the age, of the world, and of mankind. It is a wonder if we shall not soon bring ourselves to believe, that there is no other mode of existence but that in which we ourselves subsist. And yet there never was

a time, when the public was more greedy after novelty: But where

do men for the most part seek for it? In new combinations of

ancient thoughts. They examine words and phrases through a

microscope: They turn their old stock of books over and over

again: They resemble an architect, who should think of building

a city by erecting successively different houses with the same

materials. If we would seriously form new conclusions, and

acquire new ideas, let us make new observations. In the moral

and political world, as well as in the natural, there is no

other way to arrive at truth. We must study the languages, the

books, and the men of every age and country; and draw from these

the only true sources of the knowledge of mankind. This study,

so pleasant and so interesting, is a mine as rich as it has been

neglected. The ties and bands of connection, which unite

together the different nations of Europe, grow every day

stronger and closer. We live in the bosom of one great republic,

(composed of the several European kingdoms) and we ought not to

despise any of the means which enable us to understand it

thoroughly: Nor can we properly judge of its present improved

state, without looking back upon the rude beginnings from which

it hath emerged.* |

||

| N.B. | ||

|

N. B.

Resennius's Edition of the Edda, &c. consists properly of Three

distinct Publications: The First contains the whole Edda: Viz.

not only the XXXIII Fables, which are here translated; but also

the other Fables, (XXIX in number) which our Author calls in

pag. 183, the Second Part of the Edda, though in the original

they follow without interruption; and also the Poetical

Dictionary described below in pag. xix. and 189, which is most

properly the Second Part of the Edda. (vid. p. xjx.) "Philosophia

Antiquissima Norvego-danica dicta Woluspa, est pars Eddæ

Sæmundi, EDDA Snorronis non brevi antiquioris, Islandice et

Latine publici juris primum facta a PETRO JOH. RESENIO, &c.

Havniæ M.DCXXV." 4to. |

||